Every Person, Everywhere: Climate and Health at the Top of the World

“It all begins with understanding who we already are, and what we already care about – because chances are, whatever that is, it’s already being affected by climate change, whether we know it or not.” — Katharine Hayhoe

The epigraph from Katharine Hayhoe’s book Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World captivates because it both provides us with a prescription for how to connect with our respective communities around the issue of climate change but also invites us to look inward to consider the parts of ourselves we can draw on to form the foundation of this connection. As I reflect on some of the formative experiences of my own life (and the writing I have used to process these experiences), I am thrilled to realize how each may permit me to relate — in some small way — to how others are affected by the climate crisis. Indeed, as Dr. Hayhoe reminds us — every person, everywhere will feel some part of the ruination climate change precipitates.

I am the wonder in the child who “pranced down Main Street in my hometown of Olympia, Washington sporting outfits ranging from frog to jelly-fish to E. coli as a participant in the Procession of the Species, an annual artistic pageant parade that seeks to enhance cultural exchange through our mutual appreciation and respect for the natural world.”

I am the resilience in the medical student who reminded his peers that “frailty — as the word is employed in our oath — is not weakness. Rather, it is an acceptance that we are merely human, subject to the same limitations and hardships as all humans. Not all of our frailties imply impairment or deficiency. Indeed, the acceptance of our frailty may suggest resilience and offer the opportunity to truly empathize with all our relations including our future patients.”

I am the humbled global health trainee who remembered how “death began to become eerily familiar — how you start to eye each newly empty bed in Parirenyatwa Hospital with a certain degree of suspicion. Part of this familiarity is undoubtedly due to resource limitations, but another significant contributing element is that the cultural paradigm here is that you bring your loved ones to the hospital to die.”

I am the somber emergency medicine resident working during the COVID-19 pandemic who recognized that “by virtue of nothing more than our association with this public health catastrophe, medical professionals will face a degree of mistrust in the wake of this pandemic. Though we were not the ones who engineered the public health response, we were there when your loved one finally succumbed, we tried and failed to stop the unrelenting and lethal tide brought by the virus, and there will always be some who are unable to forgive us this trespass.”

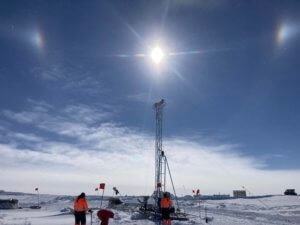

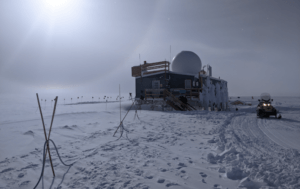

Each of these experiences inform my own connection to our planet and the people who inhabit it and therefore ultimately to climate change. Now, I sit here at the top of the Greenland Ice Cap serving as the medic for Summit Station, the National Science Foundation Arctic Research Program’s high altitude, high latitude, year-round observation outpost. As pristine a wilderness as you are likely to find, it is also remote and inhospitable at an altitude of around 10,500 ft and with temperatures ranging from an average low of -49 °F in winter to an average high of 14 °F in summer. Thanks to the remarkable resourcefulness of the human spirit and its capacity to adapt, I sit here in the company of 40 other humans responsible both for maintaining the camp and performing the science which gives this place meaning.

Here in the polar regions, it’s easy to be pessimistic when it comes to climate change. Study after study shows that the Arctic is warming as much as four times faster than other regions of the planet. And yet, I also draw inspiration from the science being conducted here. From ice core drilling to studies designed to estimate the rate at which the ice sheet is melting and breaking apart to predict the rate of sea level rise globally, my experience here will offer additional opportunities for connection around the impacts of climate change on our planet.

Each new opportunity for connection drives my own optimism. My work this year as a National Climate & Health Science Policy Fellow at the University of Colorado opened my eyes to the sobering impacts climate change will impose on our world. However, I am increasingly convinced that our response to this crisis represents an unprecedented opportunity — one that starts with a connection between people. Here at the top of the world, I’ve shared my own newfound expertise on climate change and health with the entire station at one of the station’s weekly science talks because every person, everywhere describes not only the reach of climate change’s impact but also the strategic imperative to connect on climate at every opportunity.

About Stefan Wheat, MD

Stefan Wheat, MD is an emergency physician at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and Climate Health Science & Policy Fellow at the University of Colorado. As part of his fellowship, Stefan works as a Physician-Investigator for the Department of Health and Human Services in their Office of Climate Change and Health Equity and as an Associate Research Scientist at Columbia University’s Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education. This summer he will be joining the faculty of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Washington and will continue his work on the impacts of climate change on health at the Center for Health and Global Environment.